VIDEO ACCESS RESTRICTED TO COURSE MEMBERS

To access the training video, please login to your account.

If you are not currently a member of the ARCHICAD Best Practices 2020 course, please visit bobrow.com/2020 for information and registration.

ARCHICAD Training Lesson Outline

Model Well in 3D to Draw Less in 2D

Methods, settings and approaches to 3D modeling to create clean, detailed elevations and sections.

- NOTE: Topics indicated with bullet and italics (like this note) will be presented in the next training lesson.

PRECISE MODELING CREATES CLEAN ELEVATIONS AND 3D VIEWS

When elements such as walls and slabs are stacked properly, ArchiCAD will not draw a line showing where one ends and the next one begins. The main requirements to get this result are:

- The faces must have the same surface

- They must be co-planar – correctly aligned and snapped to be precisely in the same plane

- The edges must meet cleanly, without any gaps or overlap

This works for “generic” elements such as walls, slabs, columns, beams and roofs.

Virtual Trace is helpful for ensuring that walls and other stacked elements are actually co-planar.

- TIP: Sometimes snap points are too close to easily control; for subtle alignment issues I often move node points far away from other elements, isolating one key anchor point and making sure it is properly positioned. Then I bring each one back into position and snap to the anchor point.

Note that many objects will draw their own edge lines regardless of positioning. However, some objects are “smart” enough to have a parameter or option to make certain edge lines disappear. A typical example is a cabinet which may show or hide the edge of the countertop to allow multiple cabinets appear to have a common top surface.

When the View menu > Onscreen View Options > True Line Weight is turned off so all lines are drawn as a hairline, it is easier to see the precise alignment of elements. However, to get the nicest looking drawings, from time to time it is important to inspect and adjust your drawing with true line weight turned on. One may need to change the settings of certain parts of elements; for example, window sills may default to a heavy line, and need to be revised to make them thinner.

3D Vectorial Hatching is an option in the Elevation Settings > Model View that (when turned on) shows tiles, shingles or stonework etc. based on the surface materials.

- One may adjust which pen and therefore what thickness or weight these lines will be drawn with using settings in the Options menu > Surfaces > Vectorial Hatching dialog.

It is most common to use OpenGL shading mode in the 3D Window, which represents surfaces with textured images. Sometimes it is useful to work with the same Vectorial Hatching in the 3D Window as is generated in Elevations; this can be done using the View menu > 3D View Options > 3D Styles... command or choosing one of the preset 3D Styles that includes Hatching.

To align bricks, blocks, boards or other patterns on a surface, select elements in 3D and use the Document menu > Creative Imaging > Align 3D Texture > Set Origin... command. The clickpoint can be on a corner of the element, or on any other point in the 3D model (including the corner of another element); use the same alignment point for multiple elements to get a consistent pattern.

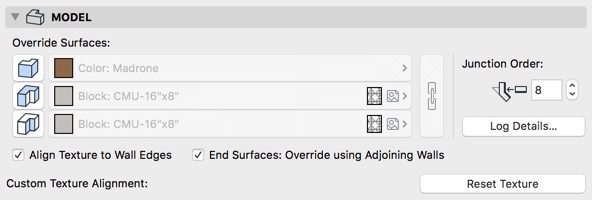

- TIP: The Wall Settings dialog provides options in the Model panel to Align the 3D Texture based on the Wall Edges, and for overriding the End Surfaces based on Adjoining Walls. There is also a Reset Texture button to return the custom texture alignment to the original setting.

SOLID ELEMENT OPERATIONS (SEO) AND COMPLEX PROFILES

Modeling 3D elements in a more sophisticated manner can add more detail to the elevations and sections. Often this is done with complex profiles to show different materials and geometry (e.g. the walls with a stone base and stucco at the top; also the cornice under the balcony).

Solid Element Operations (SEO) are often used to add more geometric detail or clean up connections or relationships between elements. For example, the ornate rafter tails are modeled using a simple object (as created by the Roof Framing wizard), then cut using an SEO subtraction to create the sculptural end.

- Similarly, the stem wall and footing is modeled with a complex profile, then this is subtracted out of the terrain mesh using an SEO.

In a section, framing may be shown using 3D elements or with 2D objects (built-in to the library or created as Patches) or simple linework. Both 3D and 2D methods may be used in the same drawing, based on your preference and level of skill. 3D approaches to framing generally are a bit more complex, but often save time when done right.

3D Framing can be done with individual elements (e.g. joists, rafters or plates made from simple or profiled beams, studs made with simple or profiled columns) multiplied with a standard spacing. Some framing can be integrated into wall profiles for plates or rim joists; other horizontal or angled framing and flashing can be done using dedicated complex profiles.

ARCHICAD Training Lesson Transcript

Hey, welcome, everyone, to the ARCHICAD Best Practices 2020 training course. Today, we’ll be focusing on modeling well in 3D so that you can draw less in 2D. Let me know that you can hear me and that you can see my screen. Use the Slack work space to communicate. If you haven’t been using Slack yet, then please go to bobrow.com/slack, and you’ll be able to put in your email address and then follow instructions and get connected in a minute or two. [0:00:45]

Alright, so I see Jimmy, Tracy, Sherry, Gestur, and Roger. OK, we’ll get going. So, the lesson right now – we’re going to be starting to transition from the foundations of using ARCHICAD effectively in terms of organizational structure. If we look at the original Best Practices course, we’ve covered weeks 1-9, pretty much. They have expanded and changed somewhat, but these first weeks – the first set of lessons, are really about getting yourself organized properly. [0:01:42]

They assume that you’re already using ARCHICAD and that you’re looking for an edge in terms of having foundation that will make your work easier. We’re now going to be shifting gears into operation of ARCHICAD in terms of modeling and defining your project and actually drawing buildings, drawing sites, putting in your design. [0:02:10]

Now, as we move into this section here, I’m referring to the original Best Practices course because I think that the outline that I had is highly relevant, but of course, some things have really developed and changed. So, for example, the Model Well in 3D section really needs to be a much bigger component, and we’re going to be spending quite a bit more time on it. Oh, I see. I just realized I’m using the one webcam, and I don’t have the other one on. OK, let me just switch this. [0:02:51]

So, just one moment, please. Let’s see here. Alright, so we have a slightly different view on me. I’m not sure which you prefer. Perhaps you can comment if you like the side view, where I’m talking to you this way, and you’re seeing over my shoulder, or do you prefer the one coming from the laptop? The one coming from the laptop is looking up a little bit. This one’s a little bit more eye level, so I think it probably works better. [0:03:37]

OK, so we’re going to be spending some more time on this modeling in 3D, to look at not only the rules for stacking elements and getting clean elevations and modeling so that your sections are clean, but we’re going to be looking in more detail at building materials, Solid Element Operations, and roof connections because they are so essential to being able to get a clean model as well as beautifully detailed sections. [0:04:10]

So, I’ve created some notes based on the original notes that I had from the earlier Best Practices course, and then I’ve expanded them quite a bit. So, we’re going to be focusing on methods, settings, and approaches in 3D modeling to create clean, detailed elevations and sections. Now, I’ll just see. What is going on? Oh, OK. There is a window here. I need to respond. What is going on here? [0:04:50]

So, there we go. OK. There. There was a little dialog that I needed to answer in GoToWebinar that was preventing me from clicking on certain things here. OK, so elevations and 3D views are actually pretty similar, in terms of their core principles, as they’ve been for more than a decade. Essentially, you want to make sure that your elements like walls and slabs and others are stacked properly so that you get a clean face without any extraneous lines. [0:05:43]

ARCHICAD is smart enough to take 2 surfaces that are coplanar, whether it’s 2 walls next to each other that have the same line and space or walls stacked on top of each other, or walls and possibly slabs that are stacked, and make a clean façade – a clean view. Now, the basic principles have not changed. The faces must have the same surface. It used to be called the same material. So, basically, if you had something that was stucco, and then you had something that was wood for the framing of the slab that was sticking out to the edge, and then stucco, you would see a line, or if you had it painted white and then grey and then white, you would see a line. [0:06:34]

If it’s the same white and white and white or stucco, stucco, stucco, or whatever, they will not show a line. ARCHICAD will remove that. The edges must meet cleanly without any gaps or overlap. Now, let me just bring up our model here, and we’ll see one of them. Actually, we’ll just go to a blank project and do some very, very quick demonstrations of this. So, I’m just going to draw 2 walls here and look in 3D, and if I select it, you can see that this is one wall. That’s another wall. We’re not seeing a line. [0:07:22]

In order to be able to tell this more clearly, I’m going to switch my 3D view style to a white model – interesting. Not very bright. Let’s see if I flip around to the other side. Alright, that’s at least a lighter side, but you can see that these 2 walls – we’re not seeing a line. Now, if the 2 walls are not quite coplanar – so, let’s say that I take one of them, and I adjust it just to be a hair off the angle. Now, they will clean up in plan nicely here, and this might be such a subtle difference – just a tiny millimeter or a fraction of an inch that you might not even see it, but if we go to 3D, we’re going to see that line because they’re no longer in the same plane. [0:08:10]

So, one of the things for clean modeling that you need to make sure of, of course, is that things are lined up. Of course, it’s better for construction in general when things line up if they’re supposed to line up. So, how would you clean that up? That’s a common question that comes up when people send me files in the coaching program and say, “This is not looking the way I need it. I’m getting some extra line work.” [0:08:39]

So, in this simple case, if I take this edge, I know this point is off, and that point is clean. You have to decide what’s the measurement point that matters. Now, in this case it’s pretty clear that this one, I drew it horizontally, and this one I took off. Sometimes, you have to just check measurements and things. For example, we can go to the Measure tool and click on this corner and click here, and it will say, “Oh, this is not at 0°. This angle is showing at 0.66°,” whereas at this snap point – when I bring it to wherever that break point is, this is at 0°. [0:09:22]

So, I know that relative to that first point that I clicked, this is exactly horizontal, and the other one is not. Now, if I want to get this lined up, and I know that this is a good point, what I can do is move this around until it’s in line. Now, in terms of guides, we’ll see that the angle here – there’s a little dashed line. This is the angle that it is, 1.64. That’s what it’s showing from the start of this piece of the wall, and this angle is 0, so we can read that off. [0:09:59]

Sometimes, it’s not easy to see that. If you press the Shift key, be aware that the Shift key may lock you in for whatever angle you’re currently on, so that doesn’t necessarily help. So, sometimes what I’ll suggest you do is move closer to this end, hold down the Shift key, and then it’s going to be locked in on the axis here. So, I can, for example, bring it while I have the Shift key held down, and stretch it until I get it in line with perhaps the original vertical location. So, at this point, when I go back to 3D, we should see this clean up. [0:10:45]

Now, let’s look at this when we have things stacked on top of each other. Now, we are going to be talking about more sophisticated ways to extend walls on top of each other, but we’re going to start with just having 2 walls stacked and putting in a slab in between or underneath and see how those work in terms of general principles. [0:11:10]

So, if I go to the Slab tool here, and I draw a slab – say, the rectangular shape like this, this slab is set to be going from 0 at its top surface – a certain thickness. In this case, it would be about 8 inches, which would be about 200 millimeters, and it’s going down because that’s the top surface reference. Now, if I go to 3D, we’re going to see this slab with extra lines. Now, why are the extra lines there? Because the slab’s surfaces are different than the wall. [0:11:51]

Now, if I turn off the white model and say to give me a 3D view, then we’ll see, of course, that they’re very different surfaces. Now, one simplistic approach that could be useful in early modeling is to simply say that this slab here – if I select it, needs to have a different surface. So, I can go and click on the option for surfaces and say I’d like to override the edge surface here with something, and not quite sure which one to use. Let’s just try the Stucco White and see if that works. [0:12:30]

OK, so that made all of these edges white, but it’s still going to be showing a line. I need to find out what the wall is or set the wall to something. So, we go into the surface here, and it says the surface here is based on the building material. So, if we were to override it like this, then it would become generic exterior, but if I don’t have it overridden, then it’s going to be based on the building materials. [0:13:02]

So, let’s see what the building materials are for this wall. If I right-click on this wall here in 3D and say Edit Selected Composite, this will allow me to see that this is made out of generic exterior, then cladding, and then generic interior. So, I just drew – from the standard U.S. template – a wall with those particular building materials as an initial concept. [0:13:34]

So, what does generic exterior look like in 3D? Well, under the Options menu, building materials, I can look and say that generic exterior is using a surface called generic exterior. Well, nice that it corresponds. So, it’s made of a building material when you cut through it, and it has a surface appearance that has a name that’s similar. Let’s go now and say, “What if I make this – the faces here that I’m overriding – to be this edge instead of stucco?” Let’s make it generic exterior. [0:14:20]

Now, you can see it changed colors suddenly. When I let go or click outside it, you can see the line disappears. So, ARCHICAD is, of course, smart enough to say these 2 surfaces have the same appearance. They are precisely touching each other, and therefore, there would not normally be a line. Now, if this slab was off just a hair – so, if I use the Pet Palette here to pull this out, and if I pull out a chunk like this, you’d expect to see a line in space, but if I pulled it out just a hair – so, let me just take this 1/32 of an inch. We can see the line in space there. [0:15:14]

Now, if I go to the floor plan, we will not be able to tell visually the difference between this wall and the edge of the slab unless we zoom in really, really tight and can see that 1/32 of an inch. So, I am zoomed out a little bit. It’s going to be very, very hard to tell if that’s off. So, sometimes it’s important to find where things are broken, and I’m going to give you a tip here, and this is saying that if I decide that the wall is my defining point – in other words, if the wall is lined up properly, but I have some suspicion that the slab is not lined up right, maybe I don’t know even if the slab edge is exactly on the axis. [0:16:21]

What I’ll do is – let’s see. I’ll go and select the slab here, and I’ll go to the corner point, and I’ll reposition it. Now, I might just take it down, say, using the guideline to take it down away from this, and then take it back, and when it snaps, I know it’s going to be perfectly on that point. Sometimes, you have several elements all stacked up on top of each other, and that can be tricky. [0:16:55]

Again, remember, this is 1/32 off because I didn’t move that one. I may take this down and then take it up until I get the intersection point. Now, without having to really necessarily zoom in a lot, just by pulling it away and then pulling it back and allowing it to snap, now, when I go to 3D, of course, it’s going to be cleanly aligned. [0:17:21]

Now, when you have elements that are stacked from one story to another, these same issues and the same requirements are going to apply. So, if I go to the plan, and let’s just say we have – I’ll just copy these 2 elements to the next story. So, I’m going to go up to the second floor here, where we have nothing placed, and I’ll paste them in. Whoa, pasting in some text. That’s not what I wanted. [0:18:02]

Select these 2, copy them, go up to the second floor and paste here. Now, will we get a clean façade as we go up the building? Well, it depends on a few factors. We know when we’re pasting in things if they’re going to stay in the same position in the XY space as long as ARCHICAD doesn’t ask us. “Hey, do you want to paste this into the center or the original position?” It doesn’t ask that it’s already going to be coming in exactly in line with where it started. [0:18:42]

So, we know horizontally in the plan plane. It is in line, but let’s look in 3D. Zoom out a little bit. Looks beautiful. Now, if we zoom in on this, you can see that this slab is passing into this space, and this wall is actually stopping short, in terms of the green line. Now, this is where we’re starting to get some differences between ARCHICAD in recent years – since version 17, and the earlier versions of ARCHICAD. This has to do with things passing through each other and ARCHICAD doing some intersection calculations. [0:19:30]

So, for those of you who are veterans and have been around for more than 5 years or so, then there was a big change in 17, and hopefully you’ve all at least gotten familiar with that, and you’re using it effectively, but let’s take a look at that as part of this effort. Now, in terms of the basic things, if I take this wall down, say, to below here, you can see that there’s a gap, and of course, you wouldn’t expect it to have a smooth surface. If I take this wall up and use the Pet Palette to bring it up until it snaps, we’re going to have a lean surface. [0:20:24]

Now, of course, if the upper elements were off alignment, then we won’t have the proper arrangements, and so sometimes, you need to use virtual trace. So, let’s just force this issue a little bit and look at how virtual trace can help make sure that things are properly aligned. So, here, I’m on the second floor, and I’m going to go right-click on the first floor and say Show As Trace Reference. You see we have that extra piece of wall, so we know that’s actually from the lower story. [0:21:01]

If I try to select it, it will bring up a message saying that this element is inactive in this view because I’m in the upper story, and the lower story is just being shown as a reference. Now, for those of you who are newer at ARCHICAD, the Trace & Reference palette is controlled using this section of the tool bar. We can bring up a separate Trace & Reference palette for controls, and just for clarity while we’re teaching, I’m going to change the reference color to red so we can see that more clearly. Now, we have a clean result, but let’s just do a similar thing where we’re going to stack these things just slightly off. [0:21:49]

So, I’m going to drag them. I’ll take them up in this direction, but just a hair – let’s say 1/16 of an inch. Alright, so what is that? About one and a half millimeters or something like that, so a very tiny amount. Now, of course, if I go to 3D, as you might expect, it’s just a subtle little line there. If you cut a section, you probably wouldn’t even see a jog because it’s off by just such a tiny little fraction. [0:22:17]

Now, how would you be able to correct that and say, “Ah, there’s a line here? What’s going on? These are lined up as far as I know.” Well, of course, I copied and pasted them, and I deliberately moved them off, so I know what the problem is, but I’ve seen so many times people draw things, and they’re attempting or expecting that they’re snapping to certain other elements, and something goes off. They do things visually without care, and they’re slightly off. So, again, how would you correct this, if you didn’t know what the problem was? You just knew that you were getting this line in space. [0:22:57]

By the way, if I go to the elevation here, and I’ll go probably South Elevation here, we’re going to see that line in space, but we don’t see the line where the slab and the wall meet, and we don’t see a line where these 2 walls meet, so this this is the same clarity that we’re seeing, and in fact, this is ultimately your litmus test. Is your model cleanly done? Do the elements align properly, and are they set up with the right surfaces, in this case? [0:23:34]

So, how would we get rid of this line here, since it’s going to be hard-edged, and in this case, it would probably be inappropriate? It’s not what we want to have. Well, I’m going to go to the plan, and with the Trace & Reference showing the lower story, I’m going to zoom in here. Now, when we’re zoomed in, you can see that we’ve got some heavy lines for the wall because under the View menu, on-screen view options, we’ve got something called Bold Cut Lines. [0:24:06]

So, Bold Cut Lines will highlight the walls and actually probably columns as well. Anything that’s cut-through that’s got a structural element will just give it a slightly heavier boundary. This is not the same as true line weight. With true line weight, we can see much more definition that may be appropriate for your working drawings, but of course, it’s harder to see what’s going on with the line so thick. [0:24:37]

So, when you’re cleaning things up, you’ll want to go and turn off true line weight if you have it on, and then you may want to go and turn off bold cut lines so that we just see everything with a uniform weight. Now, this is far enough off that I can see it. Sometimes, it can be so close. I mean, this was 1/16 of an inch or a millimeter and a half, but sometimes it can be so close that you can’t really see, so again, how would we deal with it? [0:25:14]

You have to decide what’s going to be your anchor. Is the lower story the one that looks like it’s clean, and you’re going to make the upper story line up to it? That would be a common thing. Is this corner over here the one that’s good? You verified that that makes sense. Maybe the left side of the building – all is lined up nicely, but the bottom of the building has a funny angle here, so you decide what point is your reference, and then, in this case, I’m going to go and select the wall, and again, what I suggest is that you may want to – of course, I could drag the wall up and down as a whole, but sometimes you don’t quite know if it’s horizontal or not, so again, I would say to move this off, and then move it back. [0:26:09]

In fact, actually, let’s just say to move that off and take this slab and move its corner off. So, I’ve now got things totally askew. The other side of the wall and the other side of the slab haven’t been touched, but now, I have only one point here. Now, are these really aligned? Is there actually only one snap point? In certain cases, you may have 3, 4, 5, 6 elements, all coming to a point, and not exactly right. Ultimately, you’ll need to move as many of them away as you need to and then go and say to take this point and snap it into position. [0:26:52]

Take the other point here, and snap it into position. Now, of course, this is one corner, and we know the other corner was moved as a whole, so I’m going to have to go for the same thing here and possibly move this off, and then move it back and find where the snap point is – the black pencil, and now this is a line. Now, the edge of the slab here? I would also have to do that, and again, I’ll just move it off and then move it down, and you can use the guidelines to make sure you’re moving things, just keeping them aligned vertically or horizontally on the axes, but now, at this point, if I go back to 3D, I’ve now cleaned up that relationship, and if I go to the elevation, we’re going to see that this elevation now doesn’t look like much of a building, but it’s all very clean. [0:27:55]

So, those are some important considerations for just making sure that things show up cleanly in an elevation, and, of course, in your 3D views as well. Let’s see if there are any comments or questions here. Alright, so a lot of things, such as hello from different people, and Chris asking, “Am I on Mojave?” I am still on High Sierra on this computer. I may go to Mojave soon. I just upgraded my other computer to Mojave, but I haven’t been using it much. [0:28:32]

I assumed, since Apple came out with that operating system back in September or October, and here we are in March, that it’s probably that ARCHICAD has been updated to work nicely, and Apple has gotten things all tweaked, so I probably will upgrade, but right now, I’m using the previous version of the operating system. So, Roger says, “How do you show hairlines in section?” [0:29:01]

OK, so we’re going to be going into sections shortly, and we’ll be looking at that, but basically, that true line weight – you can turn it off and on, and it will affect sections as well as elevations, so it is really the same controls there. Alright, feel free to type in more questions to Slack, and let us go back to my notes here. [0:29:30]

Alright, so we talked about having the same surface. So, in this case, we had the generic exterior surfaces as opposed to stucco or something else, and here’s a little tip. Elements or surfaces are a way of describing the appearance of something in the 3D window as well as in your elevations. The surfaces will have colors. They will have potentially some texture, in terms of a bitmap image or other rendering thing that make them not a flat color. [0:30:11]

In some cases, you may want to duplicate a surface and leave it unchanged, in terms of having exactly the same color, in order to get a line because sometimes you do want a line between 2 elements. I’ve seen this with cabinets, where you may need to have doors show up properly against the cabinet body. I haven’t seen that recently, but I remember a long time ago that when we modeled certain things, and they were literally touching each other and have exactly the same surface, that the line would disappear. [0:30:48]

We’d say, “Oh, we need to see that line,” so I would basically make another surface definition and leave the look exactly the same, but just by having a different surface – a different name, even just Surface 2 instead of Surface 1, we’d see the line. Obviously, the coplanar, we talked about. Edges must meet cleanly and without any gaps, so if there’s a gap, of course, there will be a line. [0:31:16]

Now, it used to be that if something passed through each other, they bumped into each other, that we’d see the line because they were essentially not meeting. They were passing into each other, but now, with the intersection calculations, ARCHICAD is often cleaning that up, and in fact, we’re going to be using intersections for a lot of the modeling, basically passing through the slab into the wall body so that the section can actually be defined properly. [0:31:48]

So, we’ve looked at virtual trace. We’re ensuring that these stacked elements are actually in line with each other, and as we were working with these walls and slabs, and these will work for columns, beams, and roofs if they’re stacked. Now, I’ve also talked about just moving things away from a point that maybe has got some confusion and then pulling them back to the anchoring point. [0:32:21]

Now, when you stack elements that are not walls or slabs, columns, or beams, then you may get a line. Even if it’s precisely on top, so this would happen, for example, with objects like a cabinet sitting on a floor. Even if the back of the cabinet was exactly the same surface material as the edge of the slab, the cabinet will draw lines around its body, and for the most part, that’s just perfect. It works nicely. Cabinets are one example of an object that has some special controls for the edges of countertops. [0:33:04]

So, we’ll just take a quick look at that, for those of you who haven’t already worked with cabinets like this. If I go to the library, and I do cabinet here, and we go to something like this cabinet, the symbol on the plan, in this case, does not show any end lines. That is something that you can control by using the counter edge controls. Now, this is for the 3D counter edge. If I go to the 3D here and show the edges, there’s going to be just a subtle difference here. Let’s just look very closely at that. [0:33:50]

When I switch these back to no edges, it just changed, and then on the plan, we have the representation on the plan of the edge visibility here. I can say just on the right side, for example, I’m going to see the line show up there. So, objects can have special controls for that. Obviously, it’s common to have rows of cabinets, the cabinets having a countertop or a backsplash – what do they call it? Updraft, upsplash, upskirt? I can’t remember. Outside of the U.S., I know it has a different term. [0:34:32]

These lines can be controlled so that you can lay out a number of cabinets, and it will look like one smooth surface, even though the surface is segmented and part of each cabinet. Another alternatives for cabinets is to turn off the countertop entirely and then use something like a slab and just make that slab the right shape for the entire surface, essentially like how it’s going to be fabricated in most cases, when you place an order for a countertop, and it’s fabricated to fit the conditions there. [0:35:10]

Alright, so we looked at the options for true line weight and hairline. OK, and there are some other things where you may need to just change line weights within library parts. I don’t think I’ll open up the settings for windows and sills and things like that. Just be aware that the line weight is certainly something you’re going to want to be able to adjust to get the best possible drawings out. Now, let’s look at 3D vectorial hatching here. [0:35:52]

This is something that will help you define your building surfaces and building materials in elevations and in 3D views. So, if we go back to this simple model here, let’s go to 3D and say that I want to make these walls here a different appearance on the outside. So, we’ll go here and say that we’re going to override the outside surface, and we’re going to put something – the simplest, like something like the brick. Where do we see masonry? [0:36:43]

OK, so it’s interesting. In the U.S. version, we no longer have just collections of brick in the surfaces, so we’ll just do masonry – structural here. OK, let’s just try that. That’s at least a concrete masonry unit block here, and now we’re seeing the surface with a picture map – something that represents the CMU block with thickness for the grooves for where the mortar is, etc. Now, if we go to that South Elevation here, we’re going to see, again, a similar thing, but these are pure lines. [0:37:30]

Now, in terms of the appearance here, we don’t have it set for the edge here of the slab. There are 2 ways we’re going to be dealing with this. One will be to actually pull the wall face down, and the other will be to sometimes just tell the face or the edge of the slab to use a similar material, just to override it. So, this is the simple way, when we’re just stacking things, that you’ll do that. [0:38:01]

So, I can go now to the outside surface instead of generic exterior. We’ll use that masonry structural, and then we’ll see that line work. Now, here we do have a bit of an issue, in terms of just the blocks not following this pattern. So, there are different things that you may need to do to get a clean result out of this. If we go to 3D, we’ll see the same difference here. You can see how the slab here is showing the same pattern as the wall. [0:38:44]

Now, for aligning these surface maps – so it’s basically mapping the blocks. This is not made of blocks. It just looks like it’s made of blocks. We couldn’t count the blocks directly from this. It’s not disassembling the wall into a whole bunch of little blocks. It’s just saying to cover it with the appearance of blocks. Now, the wall – if I select this wall here, there’s an option for the model to say to align the texture to the wall edges. [0:39:27]

So, what does that mean? It’s going to start a block based on the wall edges. If I turn that off and say OK, then you ca see how this has actually repositioned to a new relationship, and that would actually be seen also in the façade here in the South Elevation. So, that’s one way that we can control this. Now, another way that we will control this is to make multiple elements all have the same alignment point. So, let’s just take this one back and say that this – let me just stretch this. [0:40:11]

Going to take this overhanging piece of wall and use the Pet Palette to stretch it back to that corner. Now, why am I doing that? Because sometimes you may want to start the block at this corner rather than that corner or at a certain, specific point. So, let’s say that I wanted the whole blocks to be starting here. I can go to the Document menu, creative imaging. It’s sort of an odd place. It does relate to the imaging of your model, but I would say it really does, in this case, relate to your construction documents just as much as the imaging. [0:40:58]

We’re going to align the 3D texture and say to set the origin and click on this corner point. You can see that now, we have a hole block here. Now, of course, this one is not working. We’ve got this funny thing here. Let’s take this and do the same thing, so Document, Creative Imaging, Align 3D Texture, Set Origin, and I’m going to use the same point, saying, “Well, that’s where the blocks start.” Now you can see how it adjusts. So, I can do that for each of these as needed. [0:41:34]

So, I can take this one and do the same command. I haven’t set up a keyboard shortcut, but if you did this a lot, you’d want to have a keyboard shortcut for this. See how that just aligned? Then, of course, I could take this one as well. Now, I think you have to do them one element at a time. I don’t think you can select a whole bunch of them and align that, although that would be worth testing because that may be possible now. [0:42:06]

So, you can see that now, everything is lined up and looking clean and in the elevation similarly, it looks like it’s all one stacked surface. Now, I didn’t make the bottom slab have that, but it you’d follow the same process there. OK, so we’re going to look at how to go a little bit further in terms of adding more. By the way, this is where we were just looking at 3D vectorial hatching. [0:42:47]

The vectorial hatching is a natural part of your elevations. You can have a simplified version of the elevations and certainly in early stages of design, even though you may be saying something is bricks or blocks or boards, you may want to just have a simple planar representation to minimize the focus on the materiality and just show the larger geometric options that you’re working on, but in general, we’re turning on or have it on in the elevation settings. In the model display, we’ll frequently have settings for this particular elevation or all elevations, and we will have the uncut elements with a vectorial 3D hatching. [0:43:44]

So, if I turn that off, all of that line work would just temporarily disappear from there. Now, in the 3D view here, we are seeing the textural representation, and in general, that works very nicely. It’s very fast to look in this style, which is called OpenGL. It is something that is optimized for speed and, to some extent, for realism. That looks fairly natural, but sometimes you need to go to the View menu, 3D view options, and switch from these options that are below the separator line to the ones above, where we can see hidden line analytic representation. [0:44:34]

So, let’s look at hidden line vectorial, and we’re going to see something here. Now, this is obviously just the surfaces with clean, no lines in between them, but no vectorial hatching. We’ll go to the 3D view options and hidden line with hatching, and now we’ll see the lines that are going to be much more similar to what we have in the elevation. So, sometimes, it’s useful to switch your view in the 3D window to turn this on because this will exactly match what you get in an elevation drawing. [0:45:19]

So, instead of it being just a textured version and maybe a little harder to quite correspond, we can actually see the line work that is going to be used there. Now, let’s look at a couple of other quick options in that 3D view options. By the way, this was introduced in ARCHICAD 20 or 21. I think it was 20 – 3D styles as a way of saving styles that you can change on the fly or that you can change on the fly, but you can have saved combinations. [0:45:52]

Before ARCHICAD 20, you could do similar things, but you would just make the changes, and there would be no name for them, and so it’s a little harder to manage for the long-term, but here we have vectorial hatching turned on in this one, whereas this other combination isn’t on. That’s the difference there, and we can do the hatching with some colored shading – grey or tan or whatever color things are, but without texture and using the vectorial options, and there is a nice option for the contours here. [0:46:32]

You may have noticed that this is something that was definitely improved, probably around the same time this was introduced. The ability to have contrasts with different weights – so, you can see how these lines here are showing, and it does, actually, in this 3D view – if you use it, it will give you more of that definition that people have asked for a long time, saying, “I would like to have a heavy line around where my surfaces change,” where it’s against the sky or air here. [0:47:10]

So, we’re not seeing the lines in between stacked elements, but we are seeing them around here. Now, unfortunately, I don’t believe there’s a way to turn that on in an elevation. It would be an interesting option if they can add that, but it does give you some delineation options in that vectorial view. So, we’re not going to go into all the settings here. I just wanted to make sure you understood that this is sometimes very useful when you want to do some 3D modeling and figure out why your elevations are not quite lining up the way you want in terms of the vectorial hatching. [0:47:53]

So, you can turn this on in 3D and see exactly the same calculations as you would in the elevation view. So, I’m going to put it back to just one of our standard 3D view settings, which will then switch us back to the surface textures. OK, let’s see some comments in Slack. OK, so Chris says, “Instead of moving parts away and moving back, I find it quicker to cut to the edge.” OK, that’s an interesting thing. [0:48:24]

If something like a slab – either you already know it’s sticking out too far, or you pull it out further than it needs to, and then you use the split option to cut off at an edge and then just remove the piece. So that could work nicely. Obviously, when you have individual node points, it could be on and off in different ways that may not be quite as easy to use, but it’s an interesting option. I appreciate that. So, Taren asks about the ARCHICAD file use to illustrate a couple of the topics and surfaces. I actually did share that – a revised version of that with the textures in the Slack channel. [0:49:14]

So, if you go to the coaching calls here – this one here, I’ve got a version with the textures included. So, check that out, Taren, and I’m actually going to open that up as part of this session here because it helps to clarify some of the modeling options that will give you really accurate elevations and sections for your mode. OK, Kies. “What about showing the correct breaker blocks on the edges or plan views as continuations of the elevations?” [0:49:50]

OK, so this is an issue, and it is a limitation and a challenge for certain things. Now, let’s look at a couple of options here. So, when we turn a corner – let’s say this was the corner of the building here. So, let’s go and maybe bring ARCHICAD here. Let me eye drop this, and now I’m drawing a wall with those settings, and let’s say I’m drawing a wall along here. You can see the heavy line that is attached to my pencil is along the face of the slab, but the body of the wall is going to be outside it. [0:50:31]

If I wanted it to be on top of the slab, then I would flip this here to say that I’d like it to be on the other side, and there is a keyboard shortcut. I forget what it is to flip that. It might be C there, but let me just do this and click again. Alright, so we can see that the stacking here – it’s starting at the same bottom level. That’s because this bottom level here is exactly the same as the bottom level here, and this wall doesn’t have that issue vertically, but of course we have some funny things like how the blocks are there. [0:51:18]

Now, if I select this, and let’s use that document, creative imaging, line 3D texture, set origin, and I set it to this corner here, it did adjust, and yeah. Actually, it looks more like what I would hope. So, you may want to look at that and see if that gets you the correct representation. There are – sometimes you actually may need to draw another element, just like I said to take this surface and align it to some point over somewhere else. [0:51:59]

Sometimes, I’ll actually draw a little column or a little element of some sort and use that as a sort of snapping point, so that way I can precisely position the origin point. Occasionally, you might even do it in relationship to an opening, like we’re going to start these blocks at the corner of the window or the corner of the door. That might be an option instead of moving the window to the snap point. Maybe the window defines where you want it to start, depending upon your design choices. [0:52:34]

OK, so let us see here. OK, so Kies says, “How do you show it” – the correct bricks or blocks, I assume – “on a single skin wall?” So, I think that if I take this wall, and I switch it from a composite to a single skin like this – so, you saw a subtle difference here. So, this is now actually just made out of masonry structural, and masonry structural has the same surfaces. So, it’s actually looking just fine. I didn’t actually see a difference there. Obviously, you need to make sure that the native surface of the building material matches or that you’re overriding that surface with whatever it needs to do. [0:53:36]

Now, there is an option here that you should be aware of when you’re combining these elements. If I go to the Wall settings, there’s an option for end surfaces, override the end surface – whatever was set in here to use the adjoining wall. So, basically, it’s saying, “Alright, if I didn’t see any of this, I just want it to match what it used on the adjoining walls.” Now, let me just turn that off, and let’s see what happens. [0:54:09]

So, now you can see that there’s an extra line in there because it’s not matching the adjoining wall. If we go back in here and turn that on, and now it does look pretty good. Now, by the way, if I go in here, and you decide that you’ve lost control somehow of the alignment of it, you could say to reset the texture, and what that will do is say, “Alright, forget about me telling you to put the origin somewhere or maybe even at some odd angle. Let’s just reset the texture,” and let’s say OK. [0:54:50]

You’ll see that now, it’s obviously not looking correct, in terms of the bricks or the blocks. So, let me undo that last change, and we’ll put it back to where it looks a little bit more appropriate. So, Kies says, “I mean no return wall. I want to see the correct bricks or blocks at the end of the wall or the top of the wall.” So, you will not see it necessarily in those contexts. Let’s just rotate this around the y. I’m trying to get back in here. [0:55:29]

So, we are seeing that the vertical alignment is OK, but we’re seeing some odd shapes there. Let’s just see if I can select that. I don’t know whether we can control this effectively here. This is something that has some serious limitations to it. Let’s just take a look at the same set origin. Now, it says enter 3D location, so let’s just say if I grab this point here… Alright, so I just clicked on that corner, and you can see that it has done something here. It’s still rather odd. [0:56:18]

I don’t know of a way to necessarily get that to work. One option you may possibly consider, and I don’t know if it would work. Actually, let’s go to the plan here, and now we’re on the upper story. You can see this is the lower story. Let me just go down to the lower story, and let’s say that I eye drop this, and I draw another piece of wall here. [0:56:49]

Now, in theory, if I do this, and we go to 3D, now this is potentially controlled, but let’s see if I can get this surface here to match. I’ll go to that same command. Now’s when I really want to have that keyboard shortcut, so set origin, and we’ll go to this point there, and OK, so now it’s looking a little bit better here. Let’s pull this back to there. [0:57:32]

So, what I’ve done is I actually have a return around here, but I pulled it back to just the end. So, that certainly looks better. You can tell me if that actually would satisfy you. Now, if we look up on the top, we are not going to see the top in the same way, and so this is something that I’m not quite sure there is a solution for. Let’s see. OK, so Dan says, “Use the P key.” Oh, interesting, so if I hit P – I just hit P, and what did that do? That just flipped it, so P – OK, so you were referring to the shortcut for the flip but not for the set origin that I was talking about. [0:58:33]

So, I’m not quite sure if there’s a solution for this directly, and so let’s leave that as a case that we can’t resolve in today’s session. So, let us see here. OK, let me get back to my notes, and let’s go into the next part of it. OK, so complex profiles are going to allow you to add much more detail in your sections and your elevations as well as Solid Element Operations, so let’s switch over to the sample building, where we have certainly a bunch of these things incorporated. [0:59:24]

We’ll take a look. So, while you can create things like this stone base and the top of the stone base as individual elements, in this case, this is a single wall that has that shape. It’s a little hard to tell. If I select this one, we might see the green lines here indicating this. If I right-click on this, and we say to edit selected composite or profile, we’ll see that it has the normal wall body and these extra pieces that are defined for the geometry. [1:00:12]

Now, we’re going to be spending a lot of time on complex profiles at different points in the course, but this is the beginning sort of references, just to say that a complex profile for a wall will be a section view through that wall. The section view, then, of course, has different building components. It frequently will start out with the skins of a composite. So, for example, if we zoom in on this, we’ve got this skin being stucco, the next one in here being plywood, and we have an insulated framing space, and we have the gypsum board on the interior, and then of course, we have the top being a stone and this other type of stone or supporting part of that detail. [1:01:04]

Now, each of these is a fill here in the definition of a profile, but they represent actually building materials, so you can see in the U.S. version that the building materials have numbers, like 01, 03, 04, etc. They group things into concrete and masonry and metal, etc. So, these are the building materials that you’re going to be using throughout your model. [1:01:38]

So, this is a simple extrusion in the sense that whatever is defined here – when you draw the length of the wall, it looks the same all the way through, which is why things like framing – if you do have framing, this can be used effectively for the plate or the rim joist, things that go horizontally, but can’t be used for studs or vertical framing because the complex profile has a uniform extrusion that does not get punctuated by the vertical framing there. [1:02:15]

Now, in this case, you can see a shape here. I’m going to show you a solution for a certain type of edge condition that relates a little bit to what you’ve got, Kies. Not exactly the same, but I think you’ll understand where it can be applied. If I go to my 3D model here, and we rotate around – let’s see. If I rotate around, you’ll see an interesting condition here where the stone of the exterior wall – actually, where there’s a door and where there’s an opening punched through the whole thing. [1:03:04]

Now, in order to get this to look correct, I actually had to create a small little end cap. Now, I’m going to delete it to show you the limitations of ARCHICAD’s modeling. If I delete this, and it’ll take a moment because this is the first change I’ve made to the model, so it’s thinking about it. We’re going to give it a spinning beach ball for 20 seconds or so. When I delete it, we’ll see that wall as we were looking at with an exposed edge that doesn’t look correct. [1:03:40]

The piece that I’m deleting actually was just that stone. So, you notice that now that I’ve deleted it, the edge here is all looking like this ledger stone. Now, why is that? Because this particular wall is set to – it is a complex profile – that stone-based wall that we had, and the model is set to say that anywhere – let’s see. Generic exterior and surface override using adjoining walls. It basically, through some combination of what it’s looking at in here, it’s making the exposed edge all the same, and of course, if I deselect this, you’ll see that this is one that’s made of something. [1:04:36]

This is limestone, and this is the ledger stone, yet these are uniform, and if we were to have this wall sort of stop dead – if I were to go around and maybe extend it temporarily where it won’t connect up to a corner. If I were to demonstrate this – so, I think that point here, and I’ll stretch this, and I’ll take this past it. [1:05:11]

So, here is a very interesting little combination of things. In the wall settings, the generic exterior is that grey, and that’s what we’re seeing here. The other side is a cut, and this cut is happening because of a door. If I were to delete the door, we’ll just see these pass through each other, but basically, in order to deal with this particular condition, and certainly, this is a part of the Best Practices of knowing how to get your model constructed in a way that looks as close to the intended result as possible, I’m going to just show you again. [1:06:03]

I’m going to undo the extensions, and now it meets at the corner, and I’m going to undo the deletion, and I’m waiting. There we go. OK, it came back, so let’s look at what that piece is. You can see it’s a thin little piece. It does not actually connect up to the whole wall. If I say that I’d like to edit it, it is not the stone-based wall. It’s the stone-based wall cap. [1:06:36]

I think that’s what it’s called – wall end. Stone-based wall end, and you can see it’s just the bottom part here, and so, when I created this as a separate piece, I basically said to just show it with its natural ends. Don’t override the ends with grey or anything else, and so that allows, in the 3D view, for it to look natural there. So, that is something that sometimes you need to add extra pieces to cover up the ends of things and have it look correct. [1:07:23]

So, that will be helpful in certain cases. Let’s take a look at the next thing. So, I do see a question or a comment from Roy. “Can you create your own building materials in ARCHICAD?” Yes, you can. We’re going to be spending time looking at them during the course. I will be showing you a little bit about how you can manage the building materials and briefly talk about creating your own in that context today. [1:07:57]

So, we are at an hour and 10 minutes right now, so let us see here. I think probably, for today, a good stopping point will be just to look at a couple of other options for adding more detail to your model with the complex profiles and the Solid Element Operations, and then in the next lesson, we’ll spend time on sections and how the intersections of different elements using building materials will get drawn correctly, if you do it right. [1:08:40]

So, let’s take a look at the other uses of complex profiles in terms of just having detail in the model, and again, this is an orientation to the key principles. I’m going to definitely need to be spending quite a bit of time teaching the details of complex profiles and the details of building materials, but right now, I just want to say how this works, in terms of getting a nice-looking model and clean-looking drawings. [1:09:14]

So, if I go to – we’ll do… OK, we’ll go out to our original view here, and I’m going to turn on a different layer combination, where I have Solid Element Operators visible. So, SEO, in ARCHICAD’s environment, stands for Solid Element Operators or Operations, and Solid Element Operations are basically modifications of one or more elements by one or more other elements, and a common thing is to subtract spaces – subtract out parts of an element using the geometry or another one. [1:10:02]

Now, when I turn on this layer combination, we’ll see a bunch of stuff show up. So, what are we seeing up in this area? Well, if I zoom in on it, you’ll see this rather odd shape here. Alright, so this is a complex profile. I’m just going to open up the definition of it, and it is, in MasterTemplate, a rafter tail cutting tool. So, it’s basically designed as a shape that you will not see in the model but will carve out some shapes from the model. [1:10:41]

You can see some shapes that are defined. These are actually just lines, so in a complex profile, lines can be drawn for drafting purposes, but the only thing that’s going to be seen in 3D or affect things in 3D is whatever you have for fills – the fills being solid areas, and if I to select all fills, we’re going to see that there’s only one here, and this particular profile is set up to do one particular cut, but it has a bunch of other ones set in here, so if you didn’t want to have a different shape for the rafter tails, you could change this to use one of these other shapes and line it up on whatever the angle is of the rafter tail – the roof angle – and make it cut out. [1:11:37]

Now, you can see that this shape right here is the rafter tail that we’re going to get. Actually, it’s going to be coming down and around like that. So, this is what it’s cutting. If I go back to the 3D view, we can see that it is cutting there. Let me just rotate around here, and you’ll see when we zoom in on it, we can see a rafter tail here. I’m not sure if we have any other ones right in that area, but if we look up in the upper area, we can see these rafter tails that are basically rectangular extrusions or angled rectangles that have been cut off by the Solid Element Operations. [1:12:26]

So, without going into detail on the mechanics of this, the Solid Element Operations are creating a more detailed model. Now, this is one way to do it. Another way that you can get a similar effect is to have the actual shape as a profile. So, this – in this case, this rafter tail, which is just a stub because it’s not really the rafter going and supporting the roof. It’s an ornamental part of the design. This one itself – if I were to go and say to edit this selected composite or profile, it is the actual volume that you would expect to see in the 3D view. [1:13:15]

So, complex profiles can be positive spaces, in terms of volume, or negative. Now, one of the things we have in version 22 is this little triangle. This indicates that this edge here could be offset using what’s called an offset modifier. You can see it’s called rafter length in this case. So, what became possible in version 22 is to have a base definition that could be any length. Essentially, we can pull this out or even potentially back to about this point here, and it can fit a variety of contexts. [1:13:53]

This was not nearly as flexible before version 22 because basically each profile would have a fixed shape, and if you wanted to have ones with different lengths, you had to create different variations of them, but this now can be multiple ones. So, that’s another example of a complex profile, and in fact, I would say that in general, that would be that I’d recommend for something like the rafter tails now. I actually retained in the sample project the older way of doing it because it can be a good learning tool, and one nice thing about this is that you could change that cutting profile once, and all of the rafters would be trimmed to the new profile. [1:14:42]

So, you could change the design in that one place, and all of that would change. Here, it might be a little bit more difficult because of the way the management would be done. Let’s look at another example of a complex profile in the context of framing. So, we’re going to go here to one of the sections, and so we’ll be spending time on sections in the next lesson, but if we zoom in here, and I select this, you can see that what is highlighted is this vertical board – the one on the diagonal and the tongue in groove underneath the roof edge. [1:15:33]

So, this is a complex profile that can be either run the entire length of the roof edge or in between the rafter tails, depending on how you want to model it, but I believe – I think, in this case, I have it running the entire length, and then the rafter tails are punctuating it and actually cutting holes effectively with it. So, this is done with the Beam tool, in this case. You could potentially do the same thing with the Wall tool with this shape, but obviously it’s not a wall, and the Beam tool works very effectively for it. [1:16:12]

We have, in this wall – if I select this wall, here we have some interesting definition. Now, it was a question earlier about how you get hairline in a section. You go to the View menu, on-screen view options, and you turn off true line weight, and now you can see this in a hairline view. Now, if you ever wanted to print that out in a hairline for just mark-up purposes, when you do the Print command or Plot, there’s an option for hairline. So, you can turn that on, and that would just force all the lines to be thin. [1:16:54]

Another option that you might have is using the pen sets, which are controlled down here. You might have a pen set where everything is – all the pens, regardless of the number, are set to be a very thin weight. So, those would be two options for output, and then for on-screen, of course, it’s controlled by the view, on-screen view options, and then the true line weight can be turned off and on. [1:17:20]

So, we have some framing here using a dedicated complex profile, and we also have the wall with framing in here. Now, we’ll be looking at more of the details of how that’s set up in the next lesson, but just wanted to point out that the complex profiles can be used for the Solid Element Operations or directly as real parts of the model – things that you see in the final view of the model, and the more that you model correctly, the less you have to draw because you can see here that this is a well-detailed section. [1:18:07]

I mean, there may be some other things that need to be added, but in general, this is getting to be pretty close to what a construction document section would be using 3D elements. We do have some 3D elements down here. So, this is an actual beam that’s providing the joist space, but we’re also doing some things. I think this one is a 2D element. So, this one here – while it could have been done in 3D, has been drawn as a 2D element. There’s no 3D view of this particular element. It’s just a symbolic representation there. [1:18:45]

So, we’ll be spending some time on sections next time to sort of talk about the best overall strategies to generate clean sections. I’m going to just finish with one visual, which is a file that Roger Schafer sent in. I want to thank Roger for sending in this question. When he sent in this file, he was – concerned isn’t quite the right word. He was basically saying, “How do I get it to do what I need?” [1:19:17]

So, his file – let’s see if I pull this back up to here. There we go. I’ll take this up to – I think we had it up on top of the slab there, and then I picked this up and did it here. Alright, so this is what he sent in. Basically, here’s the wall. It’s stacked on top of the finish floor and the floor framing elements, and then we have a rim joist and other plate, etc. This is a stepped foundation because it’s got a very steep slope, and this weep screed – he actually had this as a profile, but he didn’t know how to get it tilted properly. [1:20:12]

Now, what you saw a minute ago, before I changed it – and I’ll just undo that to this. We have the cladding pulled down here, and it actually stops at the weep screed here, and so this is how far we can now pretty easily come, in terms of modeling, and of course, that section is going to look really very clean when you cut through it. [1:20:52]

So, let’s see. Let me go to some questions before we finish up. So, Iain. “Why not edit the profile to make the sill limestone and the wall stone?” OK, so in terms of that complex wall with the stone base, in many cases, having a single wall with the extra stone will work very, very well. I had this particular issue where there was a door cut into it that the edge face – I couldn’t control it quite the way I needed to. So, I had to create a separate little piece. [1:21:43]

If we had done the entire stone as a separate piece from the wall, then it might have been simpler in the sense that the natural end of the walls would have worked fine, but this is sort of a hybrid that shows two different ways to approach it. OK, Roger says – hey, Roger. Roger’s the designer who sent in this particular context. “So, on the rafter tail, can you do an end cut at 45°?” [1:22:26]

You may be able to have a – let’s see, rafter tail end cut at 45°? OK, so I think you maybe need to cut with another element as a Solid Element Operator because there’s no way in the complex profile to just say to cut this off at a certain end. So, you end up with some limitations with this approach, but overall, it can work pretty efficiently. [1:23:02]

So, Kies says, “How do we pull the outside skin down with the slope as shown?” I’ll be showing you that next time. If you want to check out the coaching call from last Thursday, you’ll see all of the manipulations I did to take Roger’s base file to create the geometry properly, but essentially, the entire outside skin went down to a uniform level, and Solid Element Operations were used to trim off on the angle. [1:23:39]

So, that weep screed is the operator there, and Iain says, “Edit the individual fills.” You can definitely edit individual fills, but I’m not quite sure what you’re referring to, so just in terms of this particular thing, before we finish, then, if I have this element selected here, you’ll see this little indicator that a Solid Element Operation or connection operation is in effect. [1:24:12]

If I click on it, it says that it was subtracted downward from this element – the weep screed here, and it was also the target of something else. I’m not sure what, but let me just turn these off, and you’ll see that this is basically now going all the way down. This is how far I pull down the skin, and if I wanted to recreate it, I can go to the Design, Solid Element Operations palette, select this wall as the target, select the little weep screed profile – let me find where that is. [1:24:53]

Let’s see. OK, I need to carefully make sure I’m just selecting this here. I may need to use the Arrow tool, and there’s the beam. So, now it’s selecting this shape, which was done with the Beam tool, making it the operator, and then I’m going to do subtraction with downward extrusion, and this will basically say that wherever these intersect, I’m going to subtract out that shape, and everything below it downward is going to be subtracted, and now we end up with that shape. [1:25:34]

So, that’s the mechanics of that process. So, we’ll be going into some more demonstration and discussion next time for sections and how you use combinations of building materials and Solid Element Operations to create clean results for your sections. OK, so I think we’ll finish up. I know Iain, you had a couple of extra comments there. I don’t think I can really address them right now, but perhaps in a coaching call, I can explore your suggestions for dealing with the stone-based complex profile. [1:26:15]

So, thank you all for joining me today. I’m really excited to be moving us into the operations and modeling part of the ARCHICAD Best Practices 2020 course. I think it’s going to get much more visually stimulating as we look at models, and we manipulate them and manipulate drawings. The first part – I felt like it was so important just to get organized and have the framework for saving time. So, whenever you’ve got something that you’ve done, you can reuse it, but of course, it is somewhat theoretical, and this is now much more visual. [1:26:55]

So, I think it’s going to be a lot of fun, and I look forward to sharing it with you, and meet back on Wednesday with more on this topic of modeling in 3D and details so that you have as little as possible to draft or to draw in 2D. This has been Eric Bobrow. Thanks for watching. [1:27:17]